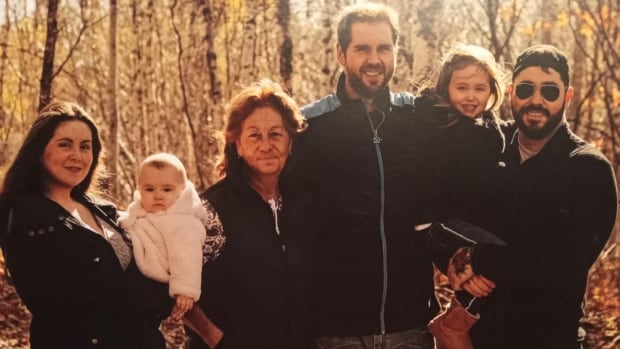

Heidi Clarke says all the warning signs should have been evident and well-documented in the days before her 25-year-old daughter Brandi died from diabetic ketoacidosis in March 2023.

That is, in essence, a death caused by a lack of insulin. As the body of someone who doesn’t have enough insulin burns off fat to create energy, because it can’t convert glucose, a chemical called ketone can build up in the blood and reach a toxic level.

It’s a hazard for anyone with Type 1 diabetes, but regular blood sugar monitoring and insulin injections can prevent it.

Brandi Clarke needed extra help to manage her condition, though. As well as being diabetic, she had been diagnosed with psychosis and was unable to look after herself, which is why she was living at a government-funded transitional housing facility in Charlottetown operated by the Canadian Mental Health Association.

Clarke said the staff there were supposed to make sure Brandi’s diabetes was being treated. She said that didn’t happen.

“No one was monitoring because if they did, they would know it,” Clarke told CBC News. “So why wasn’t anyone helping her with that? They knew she couldn’t take care of it.”

Since Brandi’s death, her mother has been searching for the answer to that question.

“No one will answer me.”

Needed supervision

Brandi had been living with her mother until she moved into a Summerside transitional housing complex run by CMHA in May of 2021. Clarke said her daughter was 23 at the time, and needed more supervision than a single working parent could provide.

“I couldn’t leave her at home. I was scared she was going to burn the house down. She would leave things on the stove.”

Brandi Clarke died from a lack of insulin while living in government-funded transitional housing. Fifteen months later, her mother is still searching for answers.

A letter from their family doctor from 2020 says Brandi suffers from Type 1 diabetes and psychosis, and “requires daily cueing and reminders to check her blood sugars/carb count and direct supervision for dosing and administration of insulin (which she requires to live but errors in administration could be life-threatening).”

The letter, which Clarke said is on file with CMHA, also said Brandi required reminders about daily hygiene tasks and supervision for things like meal preparation.

Clarke said Brandi was moved to another CMHA transitional housing facility on St. Peter’s Road in Charlottetown in September 2022 because that unit had supervision around the clock, whereas the Summerside home had no one on duty on evenings and weekends.

Mother asked about training

Clarke said the first question she asked when attending her daughter’s intake session in Charlottetown was whether staff there were trained to support a person with diabetes. She wanted to make sure they had received training similar to what Clarke herself had received from Diabetes Canada.

“I was told their people were educated,” said Clarke, but after Brandi died, “a member from CMHA told me that they were not. So I was lied to at intake.”

CMHA declined CBC’s request for an interview. Instead, the association sent the following statement:

The death of Brandi Clarke has been very difficult for her family and for our organization and its staff.

CMHA P.E.I. takes this matter very seriously, and we have been in communication with Heidi Clarke and have met with her personally. We remain committed to maintaining the highest standards of care, safety and support for all community members that connect with our organization.

Once again, we express our sincerest condolences to all of Brandi’s family.

Clarke still has Brandi’s glucose monitor, which records how often her blood sugar was tested, along with the results showing whether it was high, low, or under control.

According to the monitor, Brandi’s blood was tested once on Dec. 1, 2022; the next test was almost two months later, on Jan. 29, 2023. That was the last test recorded on the monitor before Brandi died in March.

Guidelines from Diabetes Canada recommend that Type 1 diabetics check their blood sugar at least three times daily so that any changes can be addressed by injecting enough insulin to stave off diabetic ketoacidosis.

It’s a horrifying story because this is a condition that is fatal, but it’s one that is entirely avoidable.— Dr. David Campbell

“It’s a horrifying story because this is a condition that is fatal, but it’s one that is entirely avoidable,” said Dr. David Campbell, an endocrinologist who teaches in the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Calgary.

Campbell has conducted extensive research on how diabetes affects people who are socially disadvantaged, particularly those experiencing homelessness.

He said managing diabetes is “an incredibly cognitively complex task” that requires a patient match insulin doses with their carbohydrate intake.

“The fact is many people struggle with this, and especially people who have cognitive challenges… It’s unreasonable to expect them to be able to do this.”

He said Brandi’s case provides a clear example of why there should be better supports in place for those who need them.

“This is not a condition that should lead to this very poor outcome, and the fact that it did should be a wake-up call to all of us.”

‘She loved life’

Clarke describes Brandi as kind and funny.

“She loved life. She just loved to travel. She enjoyed laughing with her friends.”

Clarke said it was always Brandi’s goal to help people. At one time she worked as a resident care worker. She was hoping to regain her independence, go back to school and study for a career in health care.

But Type 1 diabetes compounded her mental health issues. She had multiple hospitalizations for ketoacidosis, which has been linked to cognitive impairment.

“Every time it got worse. Her mental health declined every time,” said Clarke.

Their last contact was less than a week before Brandi died.

“Her last words were a hug, and ‘I love you, Mom.'”

Mother thought something seemed wrong

In the weeks leading up to Brandi’s death, Clarke said she could tell something was wrong because Brandi was avoiding her. She said she called staff at the facility and was assured Brandi was OK.

But in their notes on Brandi, which Clarke provided to CBC News, staff at the facility said they thought she was hallucinating and needed to see a doctor.

That, along with test results from the blood glucose monitor if it had been used, should have been more than enough to indicate Brandi was at risk from her diabetes, Campbell said.

A simple visit to the emergency department “would have been life-saving in this case,” he said.

Campbell said that too often, chronic issues like diabetes are considered secondary to mental health problems, or staff working with vulnerable clients lack the training to be able to recognize medical problems.

“That’s where our systems on the whole could do a much better job, if we had people and resources that could support people living with this complex condition in communities.”

Took months to get a meeting

Clarke said she reached out to staff with CMHA for 11 months after Brandi’s death before she finally was granted a meeting this past February with the organization’s executive director in P.E.I., Shelley Muzika.

But neither that nor a more recent meeting with P.E.I. CMHA board president Cecil Villard gave her the answers she’s looking for.

She wants to know what policies and staff training were in place when her daughter was admitted, and what changes have been made since her death.

She also has questions about the time of Brandi’s death, how her daughter was found, and whether staff cleaned her room before police or the coroner arrived.

She has also asked for, but not been given, surveillance video that would have shown her daughter in the hours before her death.

When Clarke reached out to Health P.E.I., which has a contract with CMHA and provides it with funding to house people like Brandi, she was told the agency had no authority to launch an investigation, and to contact the coroner’s office.

No decision yet on inquest

Clarke is still hoping to convince the chief coroner to call a public inquest into her daughter’s death.

In a statement, the coroner’s office told CBC News its investigation is ongoing and it hasn’t made a decision on whether it will recommend an inquest.

I don’t know where to go. I don’t know who to talk to. I can’t find help… I just want someone held accountable.— Heidi Clarke

P.E.I.’s ombud office also told Clarke it had no authority to launch an investigation into services provided by CMHA, even though those services were provided under contract with — and paid for by — the province.

“I’m just lost for words. I don’t know where to go. I don’t know who to talk to. I can’t find help,” said Clarke.

She said she’s spoken to lawyers about the possibility of suing. Some have told her it would be too expensive.

“It’s not about the money for me. I just want someone held accountable,” said Clarke.

“I don’t want anyone to go through this again, the same as what I’m going through. No one deserves this.”