Back in the 2000s, the found-footage terrors and gruesome “torture porn” subgenres dominated the horror world, thanks in large part to the success of films like Paranormal Activity, Saw, and their countless imitators. In 2014, though, Australian writer/director Jennifer Kent unleashed an all-new kind of monster with The Babadook, whose old-school depictions of an expressionist ghoul mixed with spooky sensibilities of ’60s and ’70s horror made for an experience that felt both entirely fresh and also like an earnest revival of tried-and-true terror. After initially making an impact in the festival circuit and in the indie horror world, the age of streaming has seen The Babadook become a bonafide classic, with a 10th-anniversary theatrical re-release allowing audiences who only ever saw the movie on the small screen being able to immerse themselves in its horrors like never before. The Babadook returns to theaters on September 19th, and a filmed conversation between Jennifer Kent and two-time Academy Award winner Alfonso Cuarón will follow each screening.

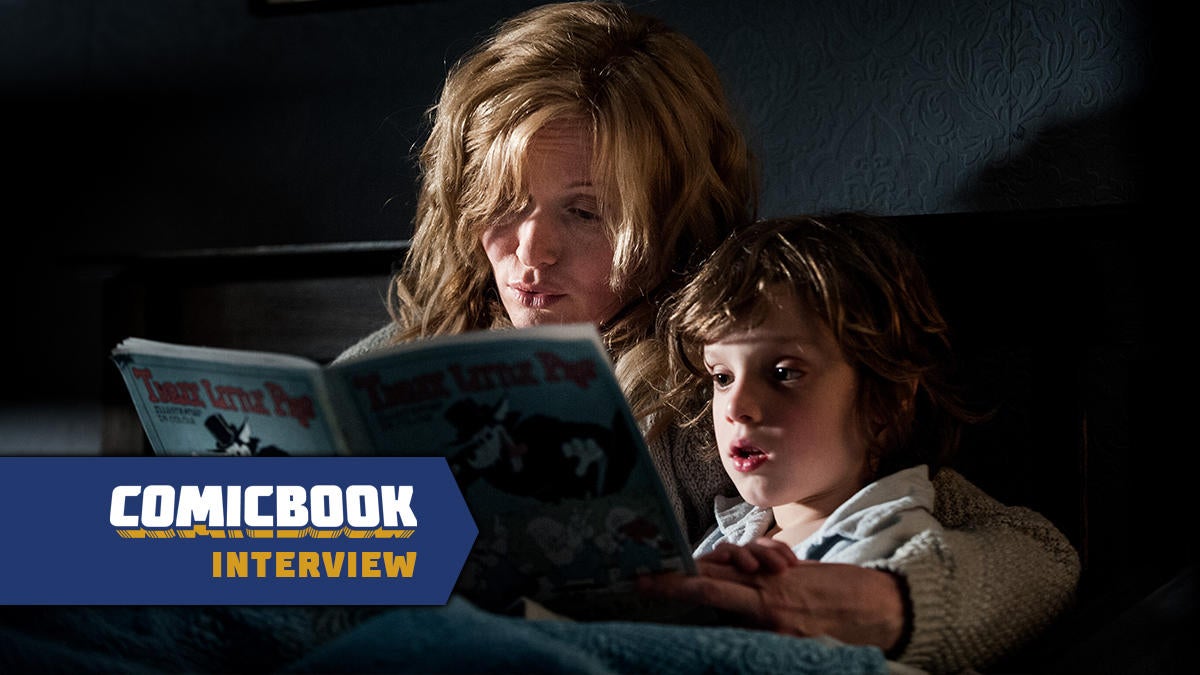

The Babadook is described, “Six years after the violent death of her husband, Amelia (Essie Davis) is at a loss. She struggles to discipline her ‘out of control’ six-year-old, Samuel (Noah Wiseman), a son she finds impossible to love. Samuel’s dreams are plagued by a monster he believes is coming to kill them both. When a disturbing storybook called ‘The Babadook’ turns up at their house, Samuel is convinced that the Babadook is the creature he’s been dreaming about. His hallucinations spiral out of control, he becomes more unpredictable and violent. Amelia, genuinely frightened by her son’s behavior, is forced to medicate him. But when Amelia begins to see glimpses of a sinister presence all around her, it slowly dawns on her that the thing Samuel has been warning her about may be real.”

ComicBook caught up with Kent to talk the cultural impact of The Babadook, watching the monster become an icon, and whether she could ever revisit that world for another installment.

The Babadook courtesy of Matt Nettheim/IFC Films

– Matt Nettheim/IFC Films)

ComicBook: I was recently looking up the history of Australian horror movies. And, of course, things that come up are Wake in Fright and Razorback and Wolf Creek. One of my personal favorites is Lake Mungo, which is a bit of an outlier. There’s such a history or a trend of arid, brutal films. Then your movie pops up and it’s just so different from every other Australian horror movie. When you were developing this movie, how did the cultural legacy of genre film from Australia impact your development, either just trying to buck the trend but not wanting to “betray” those sensibilities?

Jennifer Kent: It’s interesting that you bring that up, actually, because a lot of them are set outside, aren’t they? Australian films? Lake Mungo, to me as well, is one of our best horror movies. I adore that film and I wish that filmmaker would make more films. But, yeah, I guess I was influenced more by the interior, internal films … I’m thinking Jack Clayton’s The Innocents or the [Roman] Polanski horror particularly affected me, and Italian horror. A lot of it was expressionist and crazy and interior and in your head. That’s probably what I was looking towards, rather than sticking to my own country and the films that have gone before.

Even as you mention movies that take place outside, even just thinking of The Royal Hotel from last year, that’s another one that’s incredible and compelling, anchored by two compelling performances and a lot of it is outside.

It makes me want to go outside. Because we do live in a country with huge, vast expanses of open space that, in itself, can be terrifying. Wake in Fright, I remember seeing that and just feeling like — I was at the Sydney Film Festival because that film was lost for many years and then rediscovered. And so they did a screening at the Sydney Film Festival, and I remember thinking, “Make it stop. I can’t stand it.” But it really reflects something about the Australian psyche, certainly at that time. I think that’s why we’re always attracted by the those open spaces, which can be liberating, but also terrifying for people.

I know that the origins of The Babadook, this story, the design of the character, came from London After Midnight. While you were developing it, the name “Babadook” and the design of The Babadook, were those baked-in from pretty early on or can you talk at all about the evolution of how you landed on that name and how you landed on that design, which are now so iconic?

I think it was just a very instinctual thing. I started to think of one thing, I know I was influenced by Georges Méliès and silent cinema and those early special effects that, we look at now, and they’re very charming and hokey in a way. Certainly, Lon Cheney’s makeup is as well. There’s this old-timey feel to it, which really excited me. I thought that, somehow, is perfect because it feels like a child made it and it feels like it’s from a child’s imagination. The Babadook enters the film through Sam, because he’s the one that’s talking about it, enters through a child’s book.

These qualities made sense. As to how they played out, I think it’s, like anything that you create, one thing, one idea comes and then another comes, and who the hell knows where these ideas come from? Then it just goes to make up what it did as the script started to be developed.

Anytime I talk to someone who’s made a movie that has built like a lasting legacy, of course you didn’t know the impact this movie was going to have and the resonance it was going to have with the horror audience. But even just compared to some of the other projects that you had worked on at the time, whether it was in the writing, the filming, the editing, the actual release, was there something about it that you felt, “I’m pretty happy with what I’ve made,”? Did something feel different or unique about The Babadook as compared to some of your other projects?

Definitely. It’s worth saying that I’d written six or seven scripts before The Babadook script and I was naive. I thought, “Oh, I’m going to get money to make this film, that film.” And, of course, they were all too ambitious in their budget. And, also, I was learning how to write, how to write a script and how to perfect it, but I just actually made a conscious decision, after so many scripts got to a certain point with Screen Australia here and didn’t get made, I thought, “I’m going to write a film that is in a house with two characters,” and that was the confines that I gave myself, because then I thought, “We can make it for two million, we can make it for a million [dollars], can make it for 330 [thousand]. I just want to make this.” And that was our dedication to it. So we did it and we did get support from Screen Australia. I think the budget was $1.6 million, which we were fortunate to have that much money, even.

And then, as a first time filmmaker, you don’t know if you’re going to get through. Every day is a new experience, terrifying, vomit-inducing terror. And then it was just made, and I felt very happy with it because I had final cut. I’m very adamant as a filmmaker to have authorship of the film. I think if that film was taken away from me, it would have been destroyed, because very late in the editing process, we had a lot of criticism. People hated the film. People who had given us money did not like the film, and it was only because myself and the producers had final cut that we were able to protect that.

Speaking to the movie’s legacy, do you remember your initial reaction and where you were, the time and place, when you found out that The Babadook had become a queer icon?

Well, I was at home, I don’t know. One of my favorite shows is Drag Race, RuPaul’s Drag Race, so I was pretty chuffed about that. I think that, as it started, as the memes started coming, I think that seeing two drag queens talking about The Babadook is my idea of heaven. So I’m actually a big advocate. I bought a series of the rainbow pins, which I’ll have to dig out. So yeah, I loved it.

It is such a fulfilling, satisfying story, for as devastating as it is, has there been any interest on your part or pressure from outside sources of, “Maybe you can open up the book of Mister Babadook again?” Or is it, let me get as far away from that as I can because of how perfect of a movie that is?

[Producer] Kristina [Ceyton] and I, we could have made millions out of sequels. Absolutely. Like, no doubt. But we just … Kristina knew that I didn’t want to make a sequel. She knew that when we signed the contracts early on. We were lucky enough to have the rights, which now is really hard for filmmakers. It’s often a trade off to give away the rights to you or to any future endeavors in order to get the first one made. But with this just, I just explored what I wanted to say. It just doesn’t feel like a … You know, it could have been, but I think everyone would be really sick of Mr. Babadook by now.

The Babadook returns to theaters on September 19th, and a filmed conversation between Jennifer Kent and two-time Academy Award winner Alfonso Cuarón will follow each screening.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity. You can contact Patrick Cavanaugh directly on Twitter.