South Africans began voting on Wednesday in the most competitive election since the end of apartheid, with opinion polls suggesting the African National Congress (ANC) will lose its parliamentary majority after 30 years in government.

Polling stations opened around 7 a.m., with voters queuing at some locations including Hitekani Primary School in the vast township of Soweto near Johannesburg, where President Cyril Ramaphosa was expected to vote later.

Security guard Shivambu Yuza Patric, 48, came straight to the polling station after working a night shift. He said he had not voted in the previous election because he had lost faith in the ANC.

“They do nothing for the people,” he said. He said he would decide at the last minute who to vote for but was leaning toward small opposition party ActionSA.

Then led by Nelson Mandela, the ANC swept to power in South Africa’s first multi-racial election in 1994 and has won a majority in national elections held every five years since then, though its share of the vote has gradually declined.

If it falls short of 50 per cent this time, the ANC will have to make a deal with one or more smaller parties to govern — uncharted and potentially choppy waters for a young democracy that has so far been utterly dominated by a single party.

The ANC won 57.5 per cent of the vote in the last national election in 2019, its worst result to date and down from a high of nearly 70 per cent of the vote 20 years ago.

“There’s a lot of uncertainty with what’s going to happen. Are we going to have a coalition?” asked student and first-time-voter Amena Luke, 19, as she waited to cast her ballot at Berario Recreation Centre in Johannesburg.

WATCH | The legacy of South Africa’s 1994 election:

Get the latest on CBCNews.ca, the CBC News App, and CBC News Network for breaking news and analysis.

One-third of adults out of work

The ANC is still on course to win the largest share of the vote, meaning that its leader Ramaphosa is likely to remain president, unless he faces an internal challenge if the party’s performance is worse than expected.

Voter dissatisfaction over high rates of unemployment and crime, frequent power blackouts and corruption in party ranks lies behind the ANC’s gradual fall from grace.

The unemployment rate has hit 32 per cent, with poverty and joblessness disproportionately affecting the Black majority, who make up 80 per cent of the population of a multiracial country with significant populations of white people, those of Indian descent and those with biracial heritage.

There were 27,494 killings in South Africa in the year to February 2023, compared with 16,213 in 2012-2013. That’s a homicide rate of 45 per 100,000 people, compared to 6.3 in the U.S. and 2.25 in Canada.

The nine years of Ramaphosa’s predecessor, Jacob Zuma, were defined by what South Africans call “state capture” after an inquiry pointed to systemic corruption in which well-connected business people plundered state resources. The 82-year-old Zuma is legally barred from standing for parliament due to a jail sentence, but has formed a party, uMkhonto we Sizwe (MK), that could conceivably be part of a coalition government.

Ramaphosa succeeded Zuma as party leader in 2017 and faced questions after a large amount of cash was found hidden in furniture at his game farm. He has denied wrongdoing and was not charged with any crimes but his reputation took a hit from the incident dubbed “Farmgate.”

Turnout in South African elections has gradually dropped over the years as disenchantment with the ANC set in.

Voter wants ‘fresh minds’

Outside the polling station at Midrand High School, in a northern suburb of Johannesburg, voters waited in a long line that stretched down the street and around the corner. Some were wrapped in blankets to fend off the morning cold.

“I voted for the EFF and that’s because I need fresh minds in parliament,” said Andrew Mathabatha, 40, a self-employed engineer, who arrived early to vote there.

The Economic Freedom Fighters are a party founded by Julius Malema, a firebrand former leader of the ANC’s youth wing. The EFF wants to nationalize mines and banks and seize land from white farmers to address racial and economic disparities.

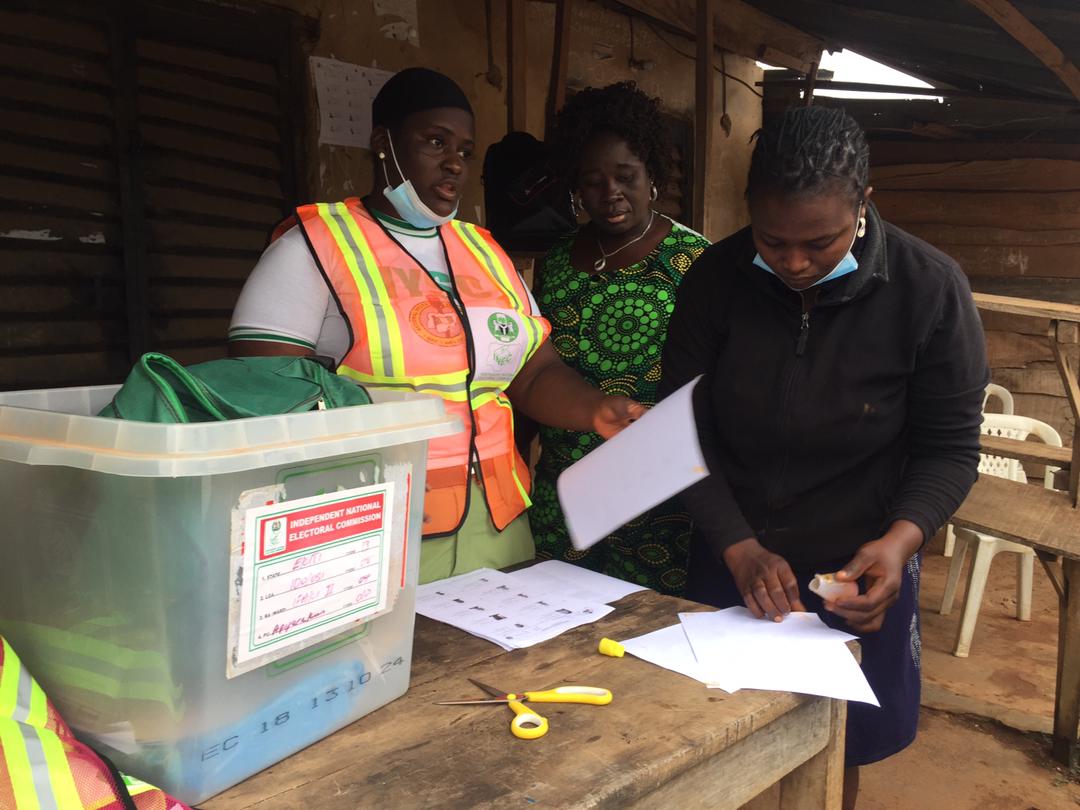

More than 27 million South Africans are registered to vote at more than 23,000 polling stations located in schools, sports centres and even a funeral parlor in Pretoria. Voting will continue until 9 p.m.

Voters will elect provincial assemblies in each of the country’s nine provinces, and a new national parliament, which will then choose the next president.

Among opposition parties vying for power is the pro-business Democratic Alliance, which won the second-largest vote share in 2019 and has formed an alliance with several smaller parties to try to broaden its appeal.

The election commission is expected to start releasing partial results within hours of polling stations closing. The commission has seven days to announce final results, but at the last election — also held on a Wednesday — it did so on a Saturday.