On Monday, if all goes as planned, a European spacecraft will blast off on a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket and begin its two-year-long voyage to a double asteroid system beyond the orbit of Mars.

The European Space Agency’s Hera mission is a follow up to NASA’s successful Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) mission, which impacted the asteroid Dimorphos in September 2022.

The goal of that mission was to demonstrate the ability to change the orbit of an asteroid. Dimorphos is the smaller of a two-asteroid system, or binary, with Didymos being the largest.

Before the DART mission, Dimorphos orbited Didymos once every 11 hours and 55 minutes. After the impact, that orbit was shortened by 33 minutes, and a plume of debris spread more than 10,000 kilometres into space, lasting for months.

WATCH | NASA slams spacecraft into asteroid to test planetary defence

NASA’s DART spacecraft slammed into the asteroid Dimorphos — 11.3 million kilometres away from Earth — to alter its orbit and test whether objects that threaten Earth can be redirected.

This smashing into an asteroid isn’t just fun and games. It has a purpose, and that purpose is for planetary defence: to test whether we can deflect an asteroid that may one day be on its way to Earth.

Both DART and Hera are part of the Asteroid Impact and Deflection Assessment (AIDA).

“Planetary defence is an extremely important initiative worldwide because asteroid impacts are something that is proven to have happened already many times in the past [and] is something for which we have clear evidence and statistics and know is going to happen again,” Hera deputy project manager Paolo Martino said.

“So the question about asteroid impact is not if, but when.”

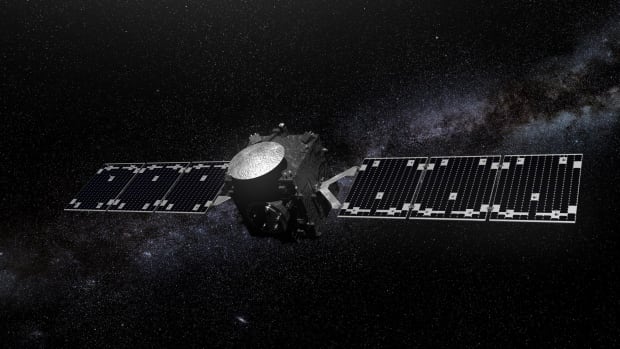

The Hera spacecraft is roughly 1.6 metres across, with solar arrays that stretch 11.5 metres once they’re fully deployed.

But Hera isn’t alone. Hitching a ride are two CubeSats, small spacecraft that have been increasingly used due to their size and low-cost.

One, Juventas, will determine the gravity field, internal structure and surface properties of Dimorphos.

The second, Milani, will map the asteroid, as well as determine the effects of the DART impact. It will also study any dust clouds around the pair of asteroids.

Eventually, the pair will land on Didymos and conduct further research on its surface composition.

New research

This follow-up mission was needed to further characterize what occurred during the DART mission.

“DART, unfortunately, couldn’t stick around once it destroyed itself on the asteroid. So we still have basic questions about what size of crater is left,” said Mike Daly, a professor at York University’s Lassonde School of Engineering in Toronto who was a co-investigator on DART.

“The shape and depth of the crater and and how much material was moved off will help refine the models of the actual process that happened. So we really have left a portion of the investigation undone with DART, and Hera is going to pick that up.”

WATCH | DART impact on binary asteroid (65803) Didymos: effects seen from the ground

Didymos, which is roughly 160 metres, is a loose collection of rocks and boulders, while Didymos is larger, at 780 metres. Most of the asteroids we’ve visited have turned out to be this type.

Hera will arrive in the asteroid system some time at the end of 2026, depending on whether or not it launches on schedule. Currently SpaceX has been grounded by the FAA following a mishap with its second-stage rocket where it did not re-enter Earth where it was supposed to after successfully launching astronauts to the International Space Station. But Martino said there is a 21-day launch window, should it be delayed on Monday.

The idea of planetary defence really hit home for space agencies in 1993 when a comet broke apart and slammed into Jupiter.

Then, in 2013, a roughly 20-metre-wide asteroid broke up in the atmosphere over Chelyabinsk, Russia. The resulting air burst injured 1,000 people.

Daly said that this AIDA mission is really the first step humanity is taking in planetary defence.

“We really are the first generation that have the knowledge and the technologies that could prevent what could be a pretty disastrous outcome on Earth,” Daly said.

“These sort of planetary protection kinds of experiments like DART and Hera, where we’re trying to better understand both the physics of these, but with an underlying idea of, okay, if we have to move one of these things, how can we do it? And how can we sure, be sure we we will be successful?”