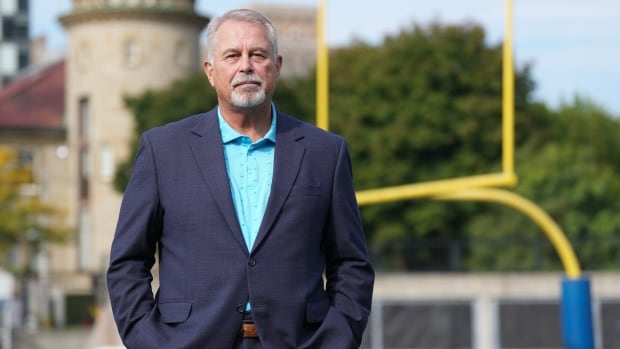

This First Person column is written by Samuel Dunsiger, a career coach and accessibility advocate in Ottawa. For more information about CBC’s First Person stories, please see the FAQ.

As I browsed through the cereal aisle. I felt myself getting light-headed. The room was spinning and I reached out to put my hand on one of the stock shelves for support. I already had a basket full of groceries, so I was trying to encourage myself to push through it.

“Only a few more items,” I told myself. “You got this.”

Only, I didn’t. The next few moments were hazy, but what I know is that I fell and started convulsing.

When I finally came to, I was on the floor, surrounded by fellow grocery store patrons, clerks and the in-house pharmacist, who told me, “You had a seizure.”

What had begun as my weekly grocery trip turned into a public — and rather unpredictable — chronic health flare-up, coupled with a dose of embarrassment and anxiety.

Public seizures

My supermarket convulsion is a manifestation of epilepsy, a neurological disorder which I was diagnosed with over 10 years ago.

I had my first seizure in my 20s during a layover at the Minneapolis airport. My parents, my brother and I were on our way to Miami to embark on a cruise and while we were waiting for our connecting flight, my arms started to jerk with uncontrollable muscle spasms.

After a few seconds, my legs started to move as well and though I maintained consciousness, I fell to the ground. My parents frantically called the paramedics. I was rushed to the nearest hospital where they told us it was a seizure.

Good thing my dad had purchased travel insurance.

When I got home, I immediately went to a neurologist for tests, which came back consistent with epilepsy.

My new diagnosis was worrisome both for me and my parents.

At that time, we didn’t know what it really meant. How often would I have seizures? Where? Could I get hurt? Could others?

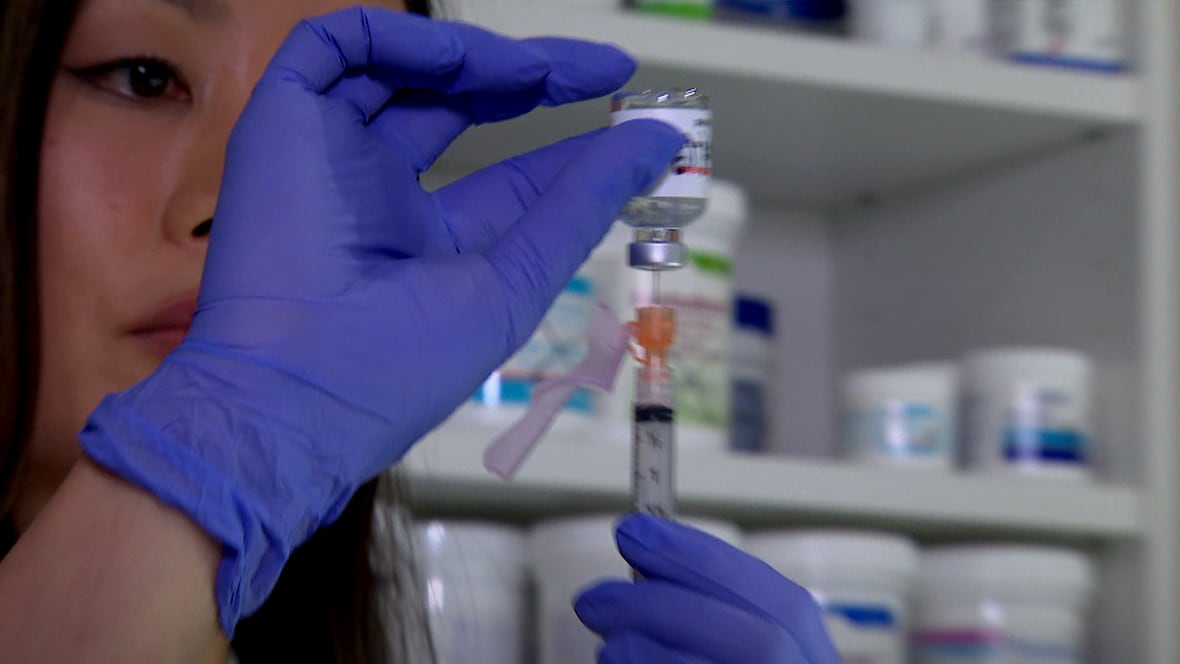

I took steps to manage it, including going on medication as well as wearing a MedicAlert bracelet with my name, condition and emergency contact.

But, I was just 26 years old. I didn’t know if my epilepsy might affect my plans to travel or live independently?

Some people with epilepsy have seizures as often as every day. A decade later, I’ve now had four seizures — one every few years.

Although I work to avoid known triggers that can prompt a seizure, such as stress, sleep deprivation or alcohol consumption, the timing of my seizures is still unpredictable.

Also, their location — though all of mine have occurred in public spaces — from Trinity-Bellwoods park in Toronto to my local grocery aisle in Ottawa.

Like an omnipresent dark cloud that refuses to go away, the uncertainty of when my next seizure will happen is always there.

Care package

After the pharmacist told me what happened, I felt the usual post-seizure symptoms of confusion, body aches, chills and nausea. One of the clerks went to grab a blanket while the pharmacist gave me a warm smile as I lay in the fetal position.

“How are you feeling?” he asked. “Can we get you anything?”

I shook my head, still feeling delirious coupled with feelings of embarrassment. Sure, I’m an expert in having epileptic episodes in public, but that doesn’t mean it gets easier.

What made it worse was imagining the scene they had just witnessed. Frightened faces looked at me. Eyes as big as golf balls. I never like being the centre of attention, and when it’s because of a chronic health issue, it makes me feel even more vulnerable.

In addition to epilepsy, I grew up with a stutter. My speech disability meant that I’ve always hated being the focus of the group. Yet here it was happening again.

Though the convulsions quickly stopped, as a pre-caution, my entourage decided to call 911.

“Great,” I thought. “More witnesses to the Friday evening seizure special spectacle at the grocery store.”

The drama continued when I was ushered out of the store on a stretcher. The pharmacist handed me a little care package of bananas, granola bars and orange juice courtesy of the supermarket.

Though I’d been through seizures enough times now to know I was likely OK, I went to the hospital just in case to reassure my family. As expected, they released me a few hours later.

The scene of the seizure

Over the subsequent days, I felt groggy but physically fine. But mentally, I felt embarrassed and uncertain, and realized I was avoiding the store like the plague.

I knew I had to return at some point. I mean, it was my nearest supermarket. So, a week later, I reluctantly returned to the scene, slowly entering through the automatic doors when I heard someone calling for me.

“I’m so happy to see you!”

It was the store clerk who had given me a blanket. To my surprise, she proceeded to give me a hug.

When I started to collect my groceries — this time, seizure-free — a few of the other clerks approached me. I even ran into the pharmacist, who again greeted me with his heartwarming smile.

Having a chronic, hidden disability like epilepsy is fraught with anxiety, uncertainty and misconceptions that I will be silently managing for life.

But, the supermarket staff’s collective kindness — even with such tiny gestures as a smile — made navigating the world with epilepsy a lot more bearable.

For me, it was a small but truly heartfelt reminder of the goodness in the world, and what a difference it can make, even if the person offering the kindness doesn’t realize its full impact.

Do you have a compelling personal story that can bring understanding or help others? We want to hear from you. Write to us at ottawafirstperson@cbc.ca.