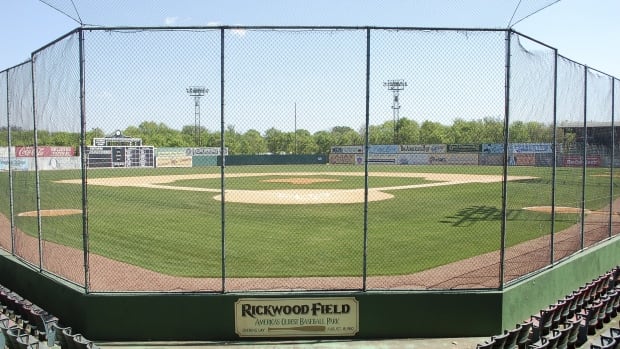

This week, in Birmingham, Ala., baseball fans will gather for a game like no other. The San Francisco Giants and St. Louis Cardinals will play at Rickwood Field, the oldest professional baseball park in the United States.

But that’s not all that makes Rickwood special. It is also the historic home of the Birmingham Black Barons, which played in the Negro Leagues between the 1920s and the 1960s — and that included baseball legend Willie Mays.

The game will be a significant moment in baseball history, as it will be the first regular-season Major League Baseball (MLB) game to be played there. The game will honour the Negro Leagues, which were made up of Black players who were excluded from the majors. In 1947, Jackie Robinson broke MLB’s colour barrier when he debuted for the Brooklyn Dodgers.

It will be held on June 20, a day after Juneteenth, a holiday commemorating the end of slavery in the United States.

“I think it’s going to be a monumental occasion on Thursday,” said Gerald Watkins, chair and executive director of Friends of Rickwood, a non-profit dedicated to preserving the park.

“This is a way to share a great story, bring attention to MLB that hasn’t been brought before, and educate a lot of people in America on the Negro Leagues and their importance.”

Here’s what you need to know.

Why is this happening?

It all goes back to the Field of Dreams. On Aug. 13, 2021, the Chicago White Sox and the New York Yankees played a regular-season game in Dyersville, Iowa, the site of the beloved 1989 movie, Field of Dreams.

“As a sport that is proud of its history linking generations, Major League Baseball is excited to bring a regular-season game to the site of Field of Dreams,” commissioner Rob Manfred said at the time.

“We look forward to celebrating the movie’s enduring message of how baseball brings people together at this special cornfield in Iowa.”

The White Sox won 9-8. The event gave Watkins an idea: What if MLB came to Rickwood?

“I envisioned Willie Mays, standing in the outfield, dreaming about being a big-league ballplayer,” Watkins told CBC News.

“I pitched that to MLB, and they got interested and came down, and we’ve been working with them nonstop to try to get ready. I’d say we’re in the eighth inning now. We’re almost there.”

The 10,800-seat ballpark, which has been renovated, will be filled with all sorts of nostalgia, like copies of old jerseys to help fans connect with its history.

The players will be wearing special uniforms that pay homage to the Negro Leagues in their respective cities.

The Giants and Cardinals will be wearing Negro League throwback uniforms for the MLB at Rickwood Field game<br><br>The threads will serve as a tribute to the San Francisco Sea Lions and St. Louis Stars Negro Leagues teams <a href=”https://t.co/Om8PL1evIK”>pic.twitter.com/Om8PL1evIK</a>

—@MLB

What makes Rickwood Field so special?

The park, which opened in 1910, has been home to 182 players who became Hall of Famers both in MLB and the Negro Leagues. But it’s never been home to a major league team.

Some of the biggest and most memorable names in baseball history have played there, including Babe Ruth, “Shoeless” Joe Jackson and Jay Dean, better known as Dizzy Dean, a pitcher who helped the Cardinals win a World Series title in 1934.

Both the Birmingham Barons and Black Barons played there, filling the stands every weekend. Willie Mays joined the Black Barons in 1948 as a teenager and soon signed with the San Francisco Giants; he played with the team from 1951 to 1972.

Mays, now 93, said that growing up nearby, Rickwood Field was “like a church.”

“The first big thing I ever put my mind to was to play at Rickwood Field. It wasn’t a dream. It was something I was going to do,” he said Monday on X, formerly known as Twitter.

“Rickwood Field is where I played my first home game, and playing there was IT; everything I ever wanted.”

A message from Willie Mays: <a href=”https://t.co/ar4dsAJDH1″>pic.twitter.com/ar4dsAJDH1</a>

—@SFGiants

Mays won’t be able to attend Thursday’s game, saying he doesn’t move as well as he used to. He will, however, be watching on television.

What else is MLB doing to honour Negro Leagues players?

Earlier this month, MLB announced it will update its database to include seven Negro Leagues to correct a “long-time oversight.” Its release will co-ordinate with the Rickwood Field game.

All of this is welcome news for Ferguson “Fergie” Jenkins, the first Canadian player inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, N.Y.

Major League Baseball is incorporating statistics from the Negro Leagues into its official record books. Ferguson Jenkins, the Hall of Fame Canadian pitcher whose father played for an all-Black baseball team in Chatham, Ont., hopes these additions spur young athletes to learn more about players from that era in baseball.

“There’s just a lot of different past history, a lot of things that people don’t know about the game of baseball and how it evolved and didn’t have players of colour play,” he told CBC News.

“I don’t think the game would be as strong [without it].”

Major League Baseball has officially added statistics from seven ‘Negro Leagues’ to its official records. The change resulted in Josh Gibson becoming the all-time leader in multiple stats, passing the likes of Babe Ruth and Ty Cobb.

Now in his 80s, Jenkins has fond memories of pitching at Rickwood Field during the 1964 All-Star Game with the Chattanooga Lookouts. He was also a guest of honour at the park in 2013 for the 18th Annual Rickwood Classic, honouring the Birmingham Black Barons.

Will Thursday’s game have a lasting impact?

Rickwood Field is already a popular tourist destination, but Watkins of the Friends of Rickwood hopes the MLB game will launch it into another league.

He also hopes it will encourage more Black youth to take an interest in baseball and, perhaps someday, play on professional teams themselves.

But even if they only watch part of the game or Google a Negro Leagues player, that will help them understand history, he said.

“I think when all of this is said and done, America is going to have a different view of baseball, and the African American kids and fans are going to have a more inclusive feel,” he said. “And hopefully, it’ll be better for our entire game.”

The proportion of Black players currently in MLB is at one of its lowest points, he noted. Indeed, a spokesperson for the league recently told the Los Angeles Daily News that about six per cent of its players are Black.

Other efforts are also afoot to further representation in baseball. The non-profit Players’ Alliance emerged in 2020 to address equity and inclusion in baseball; the following year, MLB pledged at least $100 million US to the organization over 10 years to increase Black representation.