Noah Sweeney started learning French the moment he was signed up for hockey and baseball in Quebec City as a five-year-old anglophone.

Nearly 18 years later, he is still learning — having continued his French education through elementary and high school, university and now at his job where he speaks with the majority of customers in French.

“It’s just a harder language to grasp because of all the rules,” said Sweeney.

“[It was] definitely a huge struggle. There’s only a little pocket of English people here, especially in Quebec City. Definitely was a challenge growing up.”

But he says there’s no downside to being bilingual and that, increasingly, most of his francophone friends are able to speak two languages.

As French-English bilingualism in Quebec has for the most part been on the rise since the early 1960s — with almost one in two people being able to have a conversation in Canada’s two official languages in 2021 — recent studies involving Montreal researchers now point to tangible cognitive benefits of speaking two languages.

Not only does bilingualism help maintain brain health following an Alzheimer’s diagnosis, but speaking two languages could help make the brain more efficient at any age.

That comes as no surprise to Stephen Aronson, who speaks English and French and is now learning Spanish on the popular app Duolingo.

“I think it’s good to keep those neurological pathways expanding,” said Aronson.

“I do a little bit every day and it’s sinking in. But I learned French as a kid so it comes easier.”

Processing speech in noisy environments

Acquiring a language at a younger age provides even more benefits, says Dr. Denise Klein.

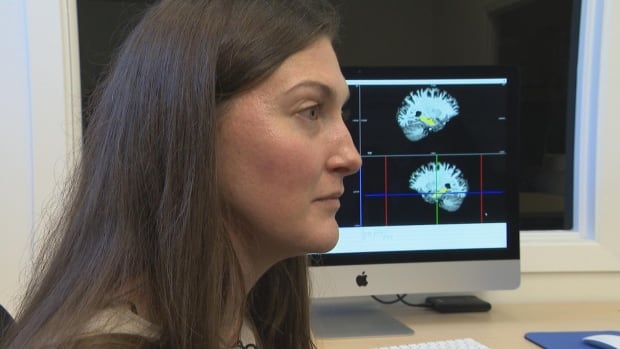

It’s part of the findings from a recent study out of the Montreal Neurological Institute-Hospital, the University of Ottawa and the University of Zaragoza in Spain.

Recruiting 151 participants who either spoke French, English or both languages, researchers recorded the age at which participants learned their second language and recorded whole-brain connectivity.

The results revealed bilingual participants had increased efficiency of communication between brain regions. This connectivity was even stronger in those who learned their second language at a younger age.

Klein, one of the study’s authors, compares learning a language at a young age to wiring a room.

“You have at the beginning sort of an empty room and you have the freedom of choosing exactly the optimal way you want to do it,” said Klein, professor of neurology and neurosurgery at McGill University.

“If later you wanted to add something, you would have to try and find an alternative route. Well, that’s probably the same with the brain.”

A new Concordia University study suggests bilingualism could delay the onset of Alzheimer’s disease by up to five years, and could even lead to greater brain maintenance.

Klein says the findings don’t show that bilingual people are better at everything, but she says bilingual people tend to be better at processing speech in noisy situations and have elevated cognitive control.

She says this study was about trying to understand how human brains become “optimal” and how language could act as a boost.

Speaking 2 languages could delay onset of Alzheimer’s

Bilingualism could actually help delay the onset of Alzheimer’s by up to five years compared to monolingual adults and have a “protective effect” on the brain as it ages, says Kristina Coulter.

The lead author behind a recent Concordia University study on bilingualism and Alzheimer’s disease, the PhD candidate said researchers compared brain characteristics of monolingual and bilingual older adults who were either cognitively normal, in decline or who were diagnosed with Alzheimer’s.

By comparing imaging of monolingual and bilingual participants who both had a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s, Coulter says they found that the size of the hippocampus was larger than expected for bilingual individuals.

In Alzheimer’s cases, among the areas often damaged first are the hippocampus and its connected structures — making it much harder for someone to form new memories or learn new information.

“What this led us to conclude was that being bilingual might actually lead to resilience … by leading to what we call greater brain maintenance,” said Coulter.

While the study did not focus on how the age of language learning might affect its benefits, she says there “isn’t anything that suggests that it won’t help.”

“Better to start than not start, no matter the age,” she said.