America has long obsessed over celebrity and the quest for fame. Thirty years ago, millions of moviegoers got to see that desire up close thanks to the groundbreaking documentary Hoop Dreams, which focused on two teenage basketball players, Arthur Agee and William Gates. The pair never fulfilled their dream of making the NBA, but Agee and Gates ended up making more of an impact than many who did.

“I always wish that we would have made it,” Gates tells the Guardian. “That feeling will never go away. I wish we would have achieved the ultimate hoop dream.”

Agee says he is still struck by the success of the documentary. “I never thought [the documentary] would be something big, let alone last for 30 years,” he says. “It’s just always surprising to me. Hoop Dreams is so much a part of pop culture now. The movie actually lives on.”

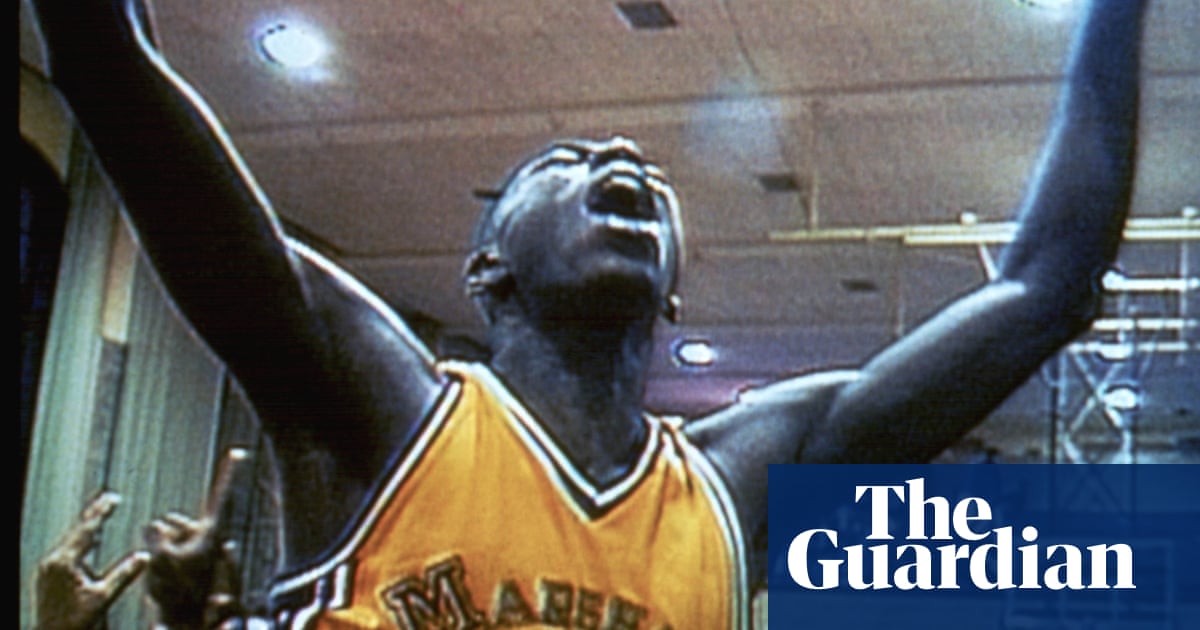

At its core, Hoop Dreams is a quintessential American story – a rags to (hopeful) riches tale. The filmmakers, director Steve James and producers Frederick Marx and Peter Gilbert, met Agee in 1987 prior to his freshman year in high school, he was a street baller then who showed great potential. Agee was invited to a summer camp at St Joseph High School outside Chicago where his idol Isiah Thomas, a two-time NBA champion, starred under longtime coach Gene Pingatore, who was still the coach when Agee arrived. It was at that camp where the filmmakers met Gates, one of the most promising young hoopers in the city. Both end up attending St Joseph but Agee is soon forced to leave when his parents can’t pay the steep tuition and his game isn’t developing as fast as his coaches want.

But the nearly three-hour movie sticks with both young guards. Gates stars at the high school and is invited to prestigious Nike showcases, but he suffers a bad knee injury, keeping him from his sky-high potential. Agee attends a Chicago public school, John Marshall High, where his team vastly overachieves. The movie ends with Gates attending the Division I school Marquette while Agee goes to a junior college.

“Being young, being 14 growing up in the inner-city of Chicago, someone wanting to invest in your life, whether they had a camera or not, I was drawn to that,” says Gates. “When [the filmmakers] asked me the question, ‘What do you want to do [with your life],’ I said, ‘I want to make it to the NBA.’ That was probably one of the most impactful questions I had ever gotten.”

“For me,” says Agee, “it was crazy because I was always enamored with television. I always wanted to be on TV. So, when the cameras came around, it was like, ‘Man, this is my opportunity!’”

The film shows their homes – in Agee’s case, at times with the electricity turned off for lack of payment – their families’ dynamics and the uphill climb (to put it mildly) both would have to achieve just to make it out of their impoverished neighborhoods. And while neither Agee nor Gates made the pros, both remain two of the most important players in Chicago’s history.

“[Hoop Dreams] shared with the world the reality of when you don’t make it,” says Gates. “There’s a lot more [people like that] on our side than the ones that make it … And what you got to do when the new dream [forms after]. Maybe it’s coaching or something else in the sport. But I had to channel what the new dream looks like at that point.”

The two remain as inseparable from each other as they are from the story of basketball itself. At first then exposure from the documentary was fun and glitzy. The two made money (though not necessarily millions) thanks to the movie’s success. They were invited to speak to schools and teams, to present at awards shows. They met political figures and rubbed elbows with celebrities at parties. Gates met Michael Jordan and later even worked out with him and was offered a workout with the Washington Wizards. But his body couldn’t hold up with his ambitions and injuries forced him to retire from the sport. Agee chased his dream of playing as far as it could take him, from college to semi-pro. He also dabbled in acting. Now, he runs a Hoop Dreams clothing line and continues to do speaking events. He and Gates, who is a preacher in San Antonio and recently published a memoir and has his own clothing line, host a Hoop Dreams podcast. And they are planning a sequel to the movie, too. But despite their fame not every door flew open.

“When I was doing the NBA thing [trying to work out for a team], it was like ‘Arthur who?’ When my agent made those phone calls, it was ‘Arthur Agee who?’” Agee says. “That’s how GMs and scouts would be. I had to go the semi-pro route. Really, the actual NBA players – those are the guys who give me and William our respect because they understood.”

Gates also experienced struggles trying to break into the pros. “I tried out for two teams,” says Gates, who broke his foot just prior to the workout with Jordan’s Wizards in the late 90s. He also gained a lot of weight at one point in his life, disillusioned with the sport. Later he slimmed down and he and Agee would run pickup games in the summers with some of the NBA’s big names, including Chris Webber and Juwan Howard.

Something the 1994 movie doesn’t go into much is just how close Agee and Gates were while the filming took place. When Agee was dismissed from St Joseph, Gates petitioned Coach Pingatore to have him reinstated. He felt lonely without him. The two talked often and would commute to the mostly white suburban school together. Prior to the film, Agee says, he looked up to Gates, who was famous even at 14, the next big thing in Chicago hoops. “Me and Will knew each other since sixth grade,” Agee says. “His elementary school and my elementary school used to play against each other. We always knew about him.”

Looking back on the movie, Agee laughs and says he wishes he read the contracts more closely. For while both got paid for their part in the doc, it was a small fraction of the money the movie made from their stories. For his part, Gates says he wishes he’d listened to his body better. When his knees hurt, he says he should have held back and not pushed himself through injury, something that led him to need knee replacements later in life.

Despite the injuries and despite Agee leaving school, both, perhaps surprisingly, express appreciation for St Joseph and the late Coach Pingatore, though they agree that the school should have made a bigger effort to keep Agee in the program. But while some might think their ups and downs in the game might lead them to despise the sport, it’s quite the opposite.

“To me,” says Gates, “the game is forever in my heart.”

“I still love the game,” says Agee. “I still play it.”

Now their children play basketball competitively, too. Agee and Gates both coach, watch the game, speak to teams and players, and share their stories. Speaking of which, while the film failed to get an Oscar nomination for best documentary – a travesty to many, including famed movie critics Siskel and Ebert, who called it one of the best films of the 1990s – Agee and Gates hope that the Academy may recognize them this year as the film approaches its 30th anniversary.

But perhaps more importantly, Agee and Gates are planning a sequel to the original Hoop Dreams, a project they’re calling After the Dream. It will include updates on their lives as well as those of other characters in the film, from best friends to late family – Agee’s father was murdered after the movie came out, as was Gates’ older brother and mentor, Curtis. The upcoming film will also show how Hoop Dreams changed basketball and movie culture. It will also be a testament to the connection Agee and Gates share.

“To always be linked with William Gates,” Agee says, “who was one of the first guards I wanted to play like – there wouldn’t be another person I would love to be linked with than him.”

“What people don’t know is me and Agee – we are so different,” says Gates. “But we can’t help but blend together. He gives me an aspect of life that I don’t have and I give him an aspect of life he doesn’t have. Those things make the greatest bonds.”