Family doctors in Ottawa are seeing an influx of public servants looking for medical notes to support work-from-home requests, putting added strain on an already overburdened health-care system.

Dr. Roozbeh Matin, who practises in Barrhaven, said he’s been noticing the trend for months, ever since the federal government announced plans to mandate public servants to work from the office more often.

“This is a systemic problem that all of us physicians in the Ottawa area are noticing,” he said. “We have been basically inundated with requests from our civil servant patients requesting various sorts of accommodation.”

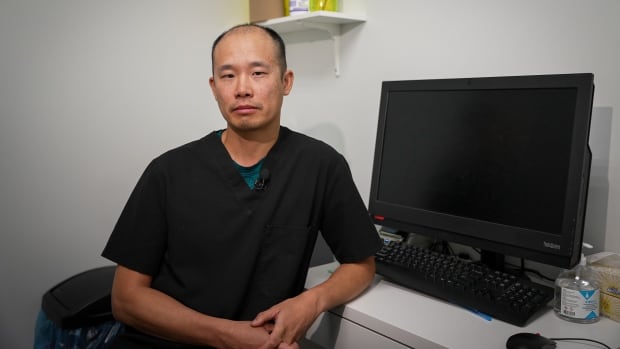

The actual numbers might not seem so daunting: Matin gets about two to four request per week, while Dr. Alex Duong has seen a few dozen since the spring at his family medicine practice in Vanier.

We’re getting completely bogged down with these requests and feeling completely overwhelmed by it.– Dr. Roozbeh Matin

But the physicians say the issue is widespread across the Ottawa area, and they see the visits — and the pages and pages of forms they generate — as a waste of scarce resources that could be going to patient care.

“We’re being asked to police these return-to-work policies for the federal government, which is frankly not an effective use of our time,” said Duong.

He said the federal government has essentially “downloaded” its own accommodation problems onto family doctors in a city where they’re few and far between.

“It’s coming at the very moment when the health-care system itself is breaking at the seams and we’re trying to desperately keep our heads afloat,” said Matin. “We’re getting completely bogged down with these requests and feeling completely overwhelmed by it.”

Paperwork ‘the bane of our existence’

It takes one full day each week for Dr. Derek McLellan to deal with all the paperwork at his Riverside South family medicine practice.

Over the past few months, patients seeking to avoid the return-to-office mandate have been adding to the heap.

“Their manager has said, ‘Well, the only way around that is a medical note, so go get one,'” he said.

If he writes one, it doesn’t end there. Patients come back with three- or six-page forms he needs to fill out. Sometimes even that isn’t enough, and they return with yet another document.

“It’s a hugely significant thing because it’s just one more task being added to our plate that is also being done, in a way, for no medical benefit,” McLellan said.

He said some of the paperwork seems all the more pointless because the patients already had remote work accommodations before the pandemic. With the return-to-office mandate, they’re now being asked to start all over again.

“This is something that’s largely an HR issue that we are being stuck in the middle of, and it’s just piling on additional administrative hours,” he said.

Duong described a similar burden. In his view, he’s being asked to do “administrative medicine” in place of “real medicine.”

“The more time I’m spending on these forms, the less time I’m able to spend on patients,” he said.

Matin said all that added work is contributing to physician burnout and affecting their ability to care for patients.

“This has generated significant amounts of paperwork, and this is the bane of our existence right now,” he said.

Doctors don’t want to play ‘gatekeeper’ for government

Matin said the reasons for the requests vary widely and include social anxiety, back pain, introversion, worries about contracting COVID-19 and gastrointestinal complaints that create an aversion to public washrooms. He said the concerns are legitimate to the patient, but they also put doctors in an awkward position.

“It puts the doctor in the situation that he has to almost do a legal adjudication, not make a diagnosis and come up with a care plan,” said Matin.

Duong said few family physicians have much training in occupational medicine, and asking them to play that role can create “friction with the physician-patient relationship.” McLellan agrees.

“You end up in a conflict because we’re positioned in the middle as a gatekeeper for this thing when there’s no medical basis for it. We have no business being involved in this conversation,” he said. “So it definitely creates some animosity.”

The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (TBS) said it does not collect information centrally on how many public servants have requested work-from-home accommodations, how many had been granted, nor how many have involved medical notes.

It pointed to the federal government’s Directive on the Duty to Accommodate, which says employees facing workplace barriers should be accommodated up to the point of undue hardship.

“The adoption of hybrid work has not altered our approach or our commitment to supporting employees,” a TBS spokesperson said in a statement.

The directive instructs managers to try to address work-related needs without resorting to a formal accommodation request, to the extent reasonable, but there might still be cases where doctors notes are necessary.

“If the barrier the employee is facing is not clear, or the potential accommodation measures are not known, supporting documentation such as medical notes may be required,” said the TBS statement. “Required documentation should be determined on a case-by-case basis, according to the specific circumstances and complexity of the request.”

Duong said there’s a simple solution: the government should hire people to produce the documents it needs

“If the federal government wants to do occupational assessments, then they should consider hiring their own physicians who are trained in occupational medicine,” he said.

McLellan has the same suggestion.

“I think that would be a far more appropriate use of resources, because then it’s their own resources,” he said. “It’s not our health system’s.”