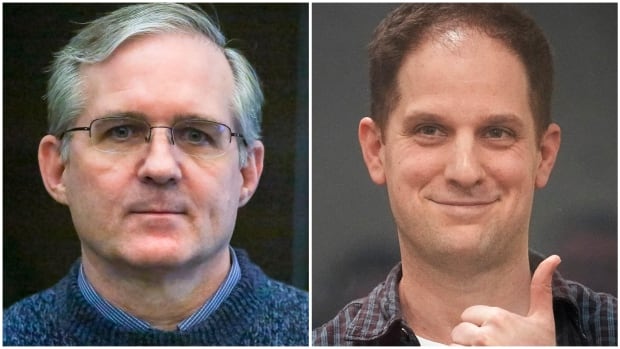

Canadian-U.S. citizen Paul Whelan and Wall Street Journal reporter Evan Gershkovich have been released from a Russian prison in an international swap deal, U.S. President Joe Biden confirmed Thursday.

Biden trumpeted the exchange as a “feat of diplomacy and friendship” calling the news an “incredible relief.” He said the detainees’ “brutal ordeal was over.”

Biden said there were 16 people released from Russia, including four from the U.S., five Germans and seven Russian citizens that were “political prisoners in their own country.”

“Today is a powerful example of why it’s vital to have friends in this world,” he said in an address from the White House while joined by families of four people — three Americans and one green card holder — who were released. Russian-U.S. journalist Alsu Kurmasheva and Russian dissident Vladimir Kara-Murza were the other two prisoners also released to the U.S. in the exchange.

The U.S. and Russia agreed to a historic multinational exchange of prisoners, including an American journalist, a Russian assassin and a Canadian who served as a U.S. Marine. Andrew Chang explains what we know about who has been freed and what still remains unclear.

Turkey, which co-ordinated the exchange, said 10 people, including two children, had been moved to Russia, 13 to Germany and three to the United States. Also involved in the swap were Poland, Slovenia, Norway and Belarus.

Biden said three U.S. citizens — Whelan, Geshkovich and Kurmasheva — were flown to Turkey and would soon be “wheels up on their way home to see their families.”

Earlier in the day, Reuters video footage showed a Russian government plane at Esenboga Airport in the Turkish capital Ankara, shortly after the Turkish National Intelligence Agency (MIT) said it was co-ordinating the extensive prisoner swap.

Whelan, 54, was arrested in 2018 and convicted of espionage two years later. He was sentenced to 16 years in prison. Both Whelan and the U.S. government have denied that he is a spy.

Born in Ottawa to British parents, he resided in Michigan for more than two decades and served in the U.S. Marines prior to his arrest in Russia.

He is a U.S. national who also holds British and Irish passports, and his detention has spanned both the Donald Trump and Biden administrations.

U.S. President Joe Biden says multiple countries joined in ‘difficult, complex negotiations’ to help craft a deal that saw 16 prisoners who were being held in Russia released, including four Americans.

Families, colleagues express gratitude for release

Whelan’s family expressed gratitude to Biden and everyone who secured his release.

“Paul was held hostage for 2,043 days,” the family said in a statement. “His case was that of an American in peril, held by the Russian Federation as part of their blighted initiative to use humans as pawns to extract concessions.”

Gershkovich was convicted of espionage on July 19 and sentenced to 16 years on charges that his employer and the U.S. have rejected as fabricated.

The conclusion of his swift and secretive trial in the country’s highly politicized legal system perhaps cleared the way for a prisoner swap between Moscow and Washington.

Gershkovich, 32, was detained in March 2023 while on a reporting trip to the Ural Mountains city of Yekaterinburg and accused of spying for the U.S., and has been behind bars ever since.

Authorities claimed, without offering any evidence, that he was gathering secret information for the U.S.

The Wall Street Journal, Geshkovich’s employer, celebrated his freedom.

“Evan and his family have displayed unrivaled courage, resilience and poise during this ordeal, which came to an end because of broad advocacy for his release around the world,” a statement from Dow Jones CEO and Wall Street Journal Publisher Almar Latour and Wall Street Journal Editor in Chief Emma Tucker read.

Russian state television showed five of 12 prisoners exchanged between Russia and Western countries as they departed from an undisclosed location. Among them are American journalist Evan Gershkovich and U.S. marine Paul Whelan.

“At the same time, we condemn in the strongest terms Vladimir Putin’s regime in Russia, which orchestrated Evan’s 491-day wrongful imprisonment based on sham accusations and a fake trial as part of an all-out assault on the free press and truth. Unfortunately, many journalists remain unjustly imprisoned in Russia and around the world.”

Speculation has mounted for weeks that a swap was near because of a confluence of unusual developments, including the startling Gershkovich trial.

In recent days, several figures imprisoned in Russia for speaking out against the war in Ukraine or over their work with the late Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny have been moved from prison to unknown locations.

Wall Street Journal reporter Evan Gershkovich was convicted in Russia on Friday of espionage charges and sentenced to 16 years in prison. U.S officials say they are trying to secure his release along with detained Canadian citizen, and former U.S. marine, Paul Whelan.

Journalist freed in time to celebrate daughter’s birthday

During his speech, Biden took the hand of Whelan’s sister, Elizabeth, and said she’d practically been living at the White House as they tried to free Paul.

He then motioned for Kurmasheva’s daughter Miriam to come closer, and took her hand, telling the room it was her 13th birthday before asking everyone to sing “Happy Birthday” with him.

The teen was emotional as Biden hugged her across the shoulders with one arm and wiped away a tear after she walked away. “Now she gets to celebrate with her mom,” Biden said. “That’s what this is all about — families able to be together again. Like they should have been all along.”

Kurmasheva, a journalist for the U.S.-funded Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, was convicted in July of spreading false information about the Russian military, accusations her family and employer have rejected.

Along with the U.S. citizens and journalists, the others released by Russia included Kara-Murza, a Kremlin critic and Pulitzer Prize-winning writer serving 25 years on charges of treason widely seen as politically motivated, 11 political prisoners being held in Russia, including associates of the late Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny, and a German national arrested in Belarus.

Germany frees high-profile Russian prisoner

The Russian side got Vadim Krasikov, who was convicted in Germany in 2021 of killing a former Chechen rebel in a Berlin park two years earlier, apparently on the orders of Moscow’s security services.

The German government said it had not taken lightly the decision to release Krasikov.

The swap was politically complicated for Germany given the brazenness of the murder, committed in broad daylight a few minutes’ walk from parliament and the office of then-chancellor Angela Merkel.

“The state’s interest in the completion of the prison sentence of a convicted criminal was counterbalanced by the freedom, physical well-being and — in some cases — ultimately the lives of innocent people imprisoned in Russia and those unjustly politically imprisoned,” the German government said.

“Our obligation to protect German nationals and our solidarity with the USA were important motivations.”

Biden acknowledged that Germany made significant concessions to achieve the prisoner swap. He told reporters at the White House that the German government had not asked for anything in exchange for its co-operation.

Russia also received two alleged sleeper agents who were jailed in Slovenia, as well as three men charged by federal authorities in the U.S., including Roman Seleznev, a convicted computer hacker and the son of a Russian lawmaker, and Vadim Konoshchenok, a suspected Russian intelligence operative accused of providing U.S.-made electronics and ammunition to the Russian military.

Norway returned an academic arrested on suspicions of being a Russian spy, and Poland also sent back a man it detained.

The exchange was the biggest prisoner swap since the Cold War. In the last major exchange in 2010, 14 prisoners were exchanged.

Whelan was detained in labour camp

Whelan spoke with CBC News from prison in March, following the death of Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny in a remote prison camp the previous month.

In a surprise call to CBC News foreign correspondent Briar Stewart in London, from the maximum security prison where he was serving his sentence, Whelan expressed hope that a deal could be reached to secure his release.

But he told Stewart that Navalny’s death — which Western governments have blamed on the Kremlin while Russia claims it was due to natural causes — showed that the fate of high-profile prisoners can change in an instant.

“If the Russian government decided they didn’t want me to leave or they wanted to pressure my four governments, they could either poison me, make me quite ill, stage an accident or do any number of things that could go wrong and lead to my death.”

Paul Whelan is more worried about his safety after the prison death of Alexei Navalny, he told CBC News in an unexpected phone call from his Russian penal colony. The Canadian-born former U.S. marine is serving a 16-year sentence for espionage.

Whelan offered a view of the conditions inside the prison camp, where he described being forced to work making winter garments for Russian utility workers, six days a week.

“It’s basically a labour camp,” he said. “It’s not a rehabilitation or correction facility.”

“The Russians always say that the poor conditions are part of the punishment, so you can just imagine what it’s like,” he said, describing the communal facility and military-like barracks where he slept in a room with 25 prisoners, and the lack of heat and hot water — even in winter.

He told CBC News he generally got along well with other inmates, although one prisoner attacked him in November.