This story is part of CBC Health’s Second Opinion, a weekly analysis of health and medical science news emailed to subscribers on Saturday mornings. If you haven’t subscribed yet, you can do that by clicking here.

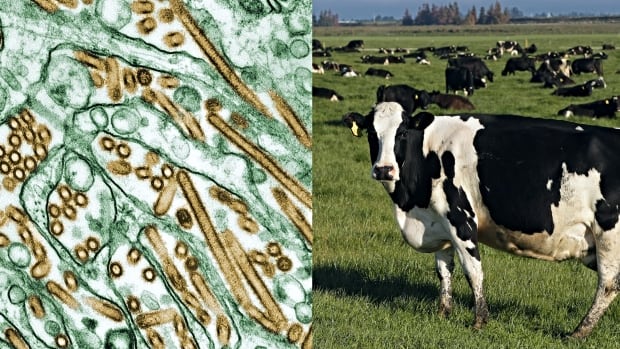

When U.S. dairy cows began falling ill with a dangerous form of bird flu, many scientists were struck by an unusual pattern: The virus kept showing up in cows’ udders, of all places.

Influenza is usually known as a respiratory virus, entering the body through the throat and nose before heading to the lungs. But Canadian virologist Alyson Kelvin wasn’t among those shocked by the udder discovery.

“We’ve known that the cow mammary gland is susceptible to influenza virus infections since at least the ’50s,” said Kelvin, a longtime influenza researcher who works at the University of Saskatchewan’s Vaccine and Infectious Disease Organization. “So this isn’t that surprising.”

Indeed, decades of scientific study provided early clues that something like this was possible.

A person in Texas who had close contact with infected dairy cattle has been diagnosed with bird flu. It’s the country’s second known human case after the virus was discovered circulating among dairy cows across at least four U.S. states for the first time.

Even though 2024 marked the first time H5N1, a form of influenza A, was reported in dairy cows, researchers knew influenza viruses can target the cells that make up mammary glands.

The little-understood transmission pathway may have also played a role in two human infections linked to the current U.S. outbreak — both of which only involved eye infections, possibly from the virus entering the eye membranes through contaminated milk.

“I think if we paid more attention to [these possibilities],” Kelvin said, “we might have not been so surprised.”

Early research showed flu can infect cow udders

So far, cases among U.S. dairy cows have officially spread to more than 50 herds across nine states.

But multiple scientists who spoke to CBC News in recent weeks say sluggish data-sharing and limited testing — and the detection of harmless viral fragments in the country’s processed milk supply — suggest the virus is already more widespread. Genetic sequencing of the virus, showing its evolution, also suggests H5N1 was likely circulating in cows months before the first cases were discovered in March.

That explosive spread appeared to come out of thin air.

Yet decades earlier, researchers from Canada’s department of agriculture were conducting “preliminary” experiments on lactating dairy cows to see what would happen when the animals were infected with several types of viruses.

Their 1953 paper showed that a type of human influenza A could infect cows’ mammary glands, leading to live virus in milk secretions.

Kelvin’s own research, published in 2015, probed the issue further.

Her team explored influenza transmission between mother and infant ferrets, an animal scientists typically rely on for flu research since ferrets’ airway receptors are the most similar to humans’.

After infecting ferrets with a type of influenza, the researchers observed several key outcomes: infant ferrets became severely ill or even died; transmission of the virus from infants back to the mother ferrets led them to develop potentially deadly lung infections; and live virus was found in both the mammary gland tissue and the mother ferrets’ milk.

“These findings suggest the mammary gland may have a greater role in infection and immunity than previously thought,” the team concluded.

Kelvin said her discoveries were met with crickets.

“I had lots of people say, ‘Who cares about the mammary glands? Why do you care about what happens if an influenza virus infects a breast?'” recalled the virologist.

“Well, I have a long list of reasons. But it was really hard to get more funding to understand the answers to those questions.”

Human cases linked to outbreak

Finding answers to how flu viruses are transmitted has perhaps never been more pressing given the ripple effects of H5N1’s unusual spread — from infections back and forth between cows and birds, to a rising number of human exposures and infections.

The two human cases linked to the outbreak so far, both among farm workers, only involved eye infections — including eye inflammation for an individual in Texas, and undisclosed eye symptoms for a more recent case in Michigan.

While it’s not clear how bird flu reaches the eye membranes, contaminated milk may play a role there as well, possibly from a “splash of contaminated fluid” or someone touching their eye with their hand, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said in a recent statement.

Earlier research also showed that simply getting virus-filled milk in the eye area could lead to an eye infection, Kelvin noted — highlighting yet another way flu viruses can spread, beyond the tried-and-true respiratory system route.

Eye infections from other forms of bird flu had been seen prior to 2018.

In those cases, the only known exposure was contact with infected poultry — often during culling operations, during which eye protection isn’t necessarily worn, one research team said.

“This suggests that ocular infection usually occurs either from workers touching their eyes with contaminated hands or from the virus traveling through the air,” the scientists wrote.

It’s possible that the virus could be spreading in a similar way now, but through cows, creating ever more opportunities for human infections.

‘It’s easy to dismiss that literature’

But before the unusual U.S. cow outbreak, there wasn’t much awareness about past research — often contained in “niche, quite often a bit older papers” — that suggested other sorts of transmission routes were possible, research virologist Tom Peacock said.

A fellow with the Pirbright Institute, a U.K.-based research organization striving to prevent and control viral diseases that can spread from animals to people, Peacock said lab-based studies may hint at the myriad ways flu can infect animals, but often, those outcomes aren’t observed in the wild.

“Prior to something like this, it’s easy to dismiss that literature,” he said. “And I think a lot of people did dismiss it incorrectly.”

The spread of H5N1 to nearly every corner of the world, even mainland Antarctica — and to a dizzying array of species, including dozens of mammals — continues to prove scientists should “expect the unexpected,” Peacock said.

One fresh case study from Michigan State University, for instance, focused on one of the state’s dairy farms and revealed striking new details on the presentation of cow infections.

The May 17 report, based on conversations with a farmer and testing on their roughly 500-cow herd, noted the farm’s outbreak began in a barn with just two pens of cattle. Yet the virus somehow spread to an estimated 40 per cent of the herd within a couple of weeks.

While earlier reporting suggested cows only experienced mild infections, the Michigan case study revealed infected cows had high fevers leading to “severe dehydration,” aborted calves and a substantial drop in milk production. Another farmer also noted symptoms sometimes lasted for four to six weeks.

Milking process could fuel transmission

What’s unique about dairy cows, immunologist Stephanie Langel said, is that their milk is used for mass production, rather than just feeding their own offspring, which could help explain these striking patterns in transmission and symptoms.

For one thing, dairy cows are milked over and over using shared equipment. New research — published online Wednesday as a preprint that hasn’t yet been peer reviewed — suggests the messy milking process could facilitate udder-to-udder transmission of H5N1 between cows, and surface-based transmission to farm workers.

Milk drips during milking, farmers spray water to clean up, and the whole process means plenty of virus-filled particles may be floating around, said Langel, a Cleveland-based researcher and assistant professor in Case Western University’s school of medicine, who wasn’t involved in the paper.

And though it’s still not clear exactly how the virus is moving cow-to-cow, it’s apparent that mammary glands are a huge reservoir containing “massive amounts” of this virus that can wind up in raw milk, Langel said.

“This is a very unique, perfect-storm kind of way that the mammary gland can serve as a vector now for transmission,” she said.

That may also help explain both the eye infections experienced by dairy workers and the dire health impacts on farm cats who drink raw, virus-filled milk.

One U.S. CDC study found more than half the cats at a Texas dairy farm died after drinking milk from infected cows, and faced systemic infections involving serious brain inflammation and high viral loads.

“The cats may be like this canary in the coal mine,” Langel said.

Scientists believe raw milk could pose a risk to humans as well, though studies suggest pasteurization ensures processed milk is safe to drink.

In another lab-based study, published as correspondence in the New England Journal of Medicine on Friday, mice that were administered raw milk from infected dairy cows experienced high virus levels in their respiratory organs, and lower virus levels in other vital organs.

“The results suggest that consumption of raw milk by animals poses a risk for H5N1 infection and raises questions about its potential risk in humans,” said the U.S. National Institutes of Health in a statement about the findings.

Burning questions still remain

Both Kelvin and Langel called for more research to better understand the complex mechanics at play when viruses infect mammary glands, and what that means for transmission to cows, humans and other species.

Effective use of personal protective equipment among farm workers is also important, farmers and medical experts recently told CBC News.

And most crucial, Langel said, is finding out how to prevent these specific kinds of influenza infections in cows’ udders in the first place. Doing so could help protect the dairy industry and slow transmission to ensure humans aren’t being repeatedly exposed to a virus, she said.

One study produced during the current outbreak, which hasn’t yet been peer reviewed, showed the cells in cows’ mammary glands can be infected by both avian and human influenza viruses, perhaps giving it opportunities to further adapt in ways that could one day facilitate human-to-human transmission.

A Quebec poultry farmer is taking extra precautions to protect his livelihood and livestock as the province grapples with avian flu outbreaks that have killed almost one million birds in the past year.

While emerging research offers new pieces to the puzzle, Kelvin said a long-standing lack of interest in maternal health has left scientists somewhat in the dark over what could come next.

It’s still not fully clear why mammary glands are susceptible to influenza, how often those kinds of infections can occur, and whether it takes a certain level of virus to sicken an animal through that transmission route, she said.

With those burning questions in mind, Langel also questioned if it’s even possible to stop the spread of H5N1 among cows, given how widespread the virus is throughout the U.S. dairy industry.

“I’m hoping that this outbreak shows we need to understand women’s health — female health, lactating animal health — more,” Langel said.