Ten minutes to play in the World Cup quarter-final last autumn, and Tadhg Beirne leaps to gather Ronan Kelleher’s throw; nine and 30 seconds, and Beirne, Kelleher, and the rest of the Irish forwards are driving together towards New Zealand’s try-line; nine left exactly, and the All Black pack has split under the pressure, and Ronan Kelleher’s driving ahead and diving over the try-line, Conor Murray riding behind him, pushing him on into Jordie Barrett’s tackle. As the three of them go down to the ground, Barrett grips Kelleher’s midriff, pulls him up, away from the turf, and flips him around just before he can get the ball down.

The replays show Kelleher was only three inches away from scoring that try, giving Ireland a one-point lead and a shot at the conversion too. Ireland’s last good chance came and went in that moment. They ended up losing by four, 28-24. Four years of work turned on a margin the length of a blade of grass. So it goes. Ireland have made it to the World Cup quarter-finals eight times, and lost every one, in every which way. They were pipped in the final minutes 19-18 by Australia in 1991, when Michael Lynagh scored in the corner, and ripped apart by New Zealand 46-14 in 2019, when the All Blacks put seven past them.

This one, in 2023, ought to have been the most painful of the lot. The joke goes that Sigmund Freud described the Irish as the only people on earth who are impervious to psychoanalysis, but a match like that, at the end of a run of results like those, would be enough to give anyone a complex. Ireland’s prop Andrew Porter has spoken about it more than once. “I’ve had to deal with sleepless nights, playing things over in your head, we were so close, and that’s why it was so gut wrenching,” Porter said. He found himself questioning whether he was even cut out to play professional rugby.

Defeat can do that to you. Look at France. They made a national project of winning that tournament, and spent the four years before it jockeying with Ireland at the top of the world rankings. They went out to South Africa the very next day, beaten by a penalty kick in the 69th minute, and five months later they’re wandering lost around this championship.

And the Irish? They’ve beaten France 38-17, Italy 36-0, and Wales 31-7, scored 15 tries, conceded three. Only one other Six Nations’ side has ever put together a run of three successive 20-point victories like this, and that was the England team which won the World Cup, who did it once in 2001 and then again in 2003. And Farrell’s side are two games away, and one-to-five on for the first of them, from doing something even Martin Johnson’s England never managed to and winning back-to-back grand slams. They are stronger, slicker, better than ever, and the gulf between them, and everyone else is as wide as the Irish sea.

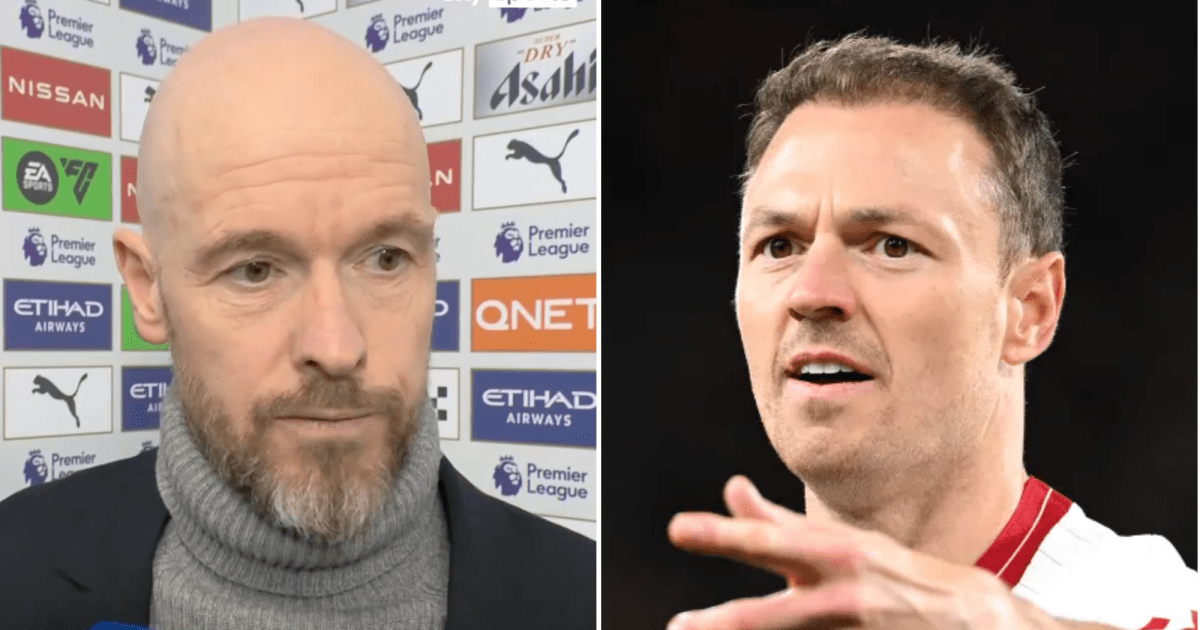

“All this talk about hangovers,” Andy Farrell said the day before his side put France away in Marseille, “There’s no hangovers with us. There’s a realisation of where we’re at and where we need to go to next, and that’s it. Hangovers are for the next day. That’s a very big hangover if you can’t get over it in three months.”

You hear so much about what Farrell won in his playing days, five championships, five challenge cups, the Super League, the Man of Steel, twice, and the golden boot too. But there’s a lot less said about how much he lost in between. Farrell played 34 Tests for Great Britain, led in 29 of them, and lost 20. His international career was essentially one long lesson in handling loss and disappointment. Most often to Australia, who beat them 13 times in 17 games and New Zealand, seven in 13 with two draws. In among them there were two excruciating defeats in the deciding Test matches of Ashes series in 1994 and 2001, and another in the Tri Nations final in 2004.

Farrell was, almost everyone who played under him agrees, one of the great captains. He took on the job when he was only 21, and did it for eight years, and long after he was gone men like Adrian Morley, who shared a dressing room with him, were still asking themselves “what would Andy do?” as they tried to find the right words to lift the team after a defeat. And it’s this quality that has made the difference for Ireland this season. Farrell is a shrewd tactician, a savvy analyst, but these last few weeks have been a testament to his man-management skills, and his understanding, honed over all those years of hard experience, of how to help his players handle defeat.

It’s a hell of a hard trick to pull off, just ask Fabien Galthié, or any number of other coaches. Eddie O’Sullivan lost his job when Ireland came fourth in the Six Nations after being knocked out in the pool stages in the World Cup in 2007, Declan Kidney’s side won a grand slam, but fell away so badly after they lost to Wales in the quarter-finals in 2011 that they lost to Italy and fetched up fifth in the championship in 2013. Even Joe Schmidt’s side, who had been No1 in the world, took a good 18 months to recover from being beaten by Argentina in the quarters in 2015, and finished third in the following year’s championship.

after newsletter promotion

Porter, who is an honest sort, said he was worried he wouldn’t ever get over the loss to New Zealand. Farrell doesn’t have much time for that sort of talk, “I’m already over it,” he said at the start of this tournament, “I don’t buy into that.” At their first team meeting this year, they had what Farrell described as “an open and honest talk” about it all, “we tried to understand it together, because that’s the only way you can move on”. The loss, he said, had given them a clear idea of where they stood, what they were good at, and what they needed to do to improve.

So they tinkered with their coaching set-up, brought in a new player or two, and got on with it. “It’s not a new start because of everything we’ve already been through,” Farrell explained, the last thing they wanted to do was “cut the legs off”, because, as he says, “that’s no way to grow”. The unavoidable truth is that sooner or later everybody loses, even sides as good as Ireland. And the difference between the great teams and the everyone else, is in what you do afterwards. “What matters now,” Farrell says, “is how you get back up.”